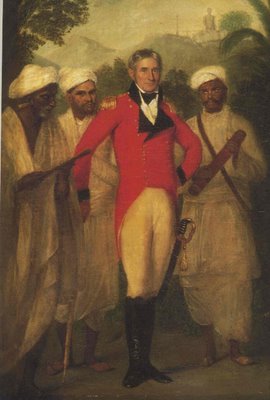

RETRATOS DE TRABALHO I - THE BRITISH RESIDENT

"Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe had been in Delhi nearly forty years by 1852, and knew well both the city and its ruler. He was a slight, delicate, bookish figure with an alert, intelligent expression, a bald pate and bright blue eyes. His daughter Emily thought “he could not be said to be handsome” but believed he did have the redeeming feature “of beautifully small hands and feet”. Certainly he was a notably fastidious man, with feelings so refined that he could not bear to see women eat cheese. Moreover he believed that if the fair sex insisted on eating oranges or mangoes, they should at least do so in the privacy of their own bathrooms.

He would never have dreamt of dressing, as some of his predecessors had, in full Mughal pagri and jama. Still less would he have dreamt of imitating the example of the first British Resident at the Mughal court, Sir David Ochterlony, who every evening was said to take all thirteen of his Indian wives on a promenade around the walls of the Red Fort, each on the back of her own elephant. Instead, a widower, he lived alone, and arranged that his London tailors, Pulford of St James's, should regularly send out to Delhi a chest of sober but fashionable English clothes.

His one concession to Indian taste was to smoke a silver hookah. This he did every day after breakfast, for exactly thirty minutes. If ever one of his servants failed to perform his appointed duty, Metcalfe would call for a pair of white kid gloves. These he would pick up from their silver salver and slowly pull on over his delicate white fingers. Then, “with solemn dignity”, having lectured the servant on his failing, he “proceeded to pinch gently but firmly the ear of the culprit, and then let him go -- a reprimand that was entirely efficacious”.

Sir Thomas had enjoyed an exceptionally happy marriage, but his wife Felicity died quite suddenly of an unexplained fever in September 1842, at the age of only thirty-four. In the decade that followed, with his six children all in boarding school in England, Metcalfe withdrew in his grief into himself. He became so set in his ways that by the time his children began returning to India in the early 1850’s, they found that their father had became a stickler for propriety and punctuality, and greatly resented any disruption to his routine. By the early 1850’s this routine was so firmly established as to be something almost set down in stone:

“He always got up at five o'clock every morning" wrote his daughter Emily, "and having put on his dressing gown he would go to the verandah and have his chota haziri [small breakfast]. He used to take a walk up and down the verandah, and his different servants came at that time to receive their orders for the day. At seven o'clock he would go down to the swimming bath which he built just below the corner of the verandah, and then having dressed and had prayers in the oratory, he was ready for breakfast at eight o'clock. Everything was ordered with the greatest punctuality, and all the household arrangements moved as if by clock work. After he had his breakfast, his hookah was brought in and placed beside his chair… When he had finished his smoke he went to his study to write letters until the carriage was announced. This always appeared at exactly ten o'clock under the portico, and he passed through a row of servants on his way to it, one holding his hat, another his gloves, another his handkerchief, another his gold headed cane, and another his despatch box. These having been put into the carriage, his Jamadar mounted beside the coachman and drove away, with two syces standing up behind…”

William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal

He would never have dreamt of dressing, as some of his predecessors had, in full Mughal pagri and jama. Still less would he have dreamt of imitating the example of the first British Resident at the Mughal court, Sir David Ochterlony, who every evening was said to take all thirteen of his Indian wives on a promenade around the walls of the Red Fort, each on the back of her own elephant. Instead, a widower, he lived alone, and arranged that his London tailors, Pulford of St James's, should regularly send out to Delhi a chest of sober but fashionable English clothes.

His one concession to Indian taste was to smoke a silver hookah. This he did every day after breakfast, for exactly thirty minutes. If ever one of his servants failed to perform his appointed duty, Metcalfe would call for a pair of white kid gloves. These he would pick up from their silver salver and slowly pull on over his delicate white fingers. Then, “with solemn dignity”, having lectured the servant on his failing, he “proceeded to pinch gently but firmly the ear of the culprit, and then let him go -- a reprimand that was entirely efficacious”.

Sir Thomas had enjoyed an exceptionally happy marriage, but his wife Felicity died quite suddenly of an unexplained fever in September 1842, at the age of only thirty-four. In the decade that followed, with his six children all in boarding school in England, Metcalfe withdrew in his grief into himself. He became so set in his ways that by the time his children began returning to India in the early 1850’s, they found that their father had became a stickler for propriety and punctuality, and greatly resented any disruption to his routine. By the early 1850’s this routine was so firmly established as to be something almost set down in stone:

“He always got up at five o'clock every morning" wrote his daughter Emily, "and having put on his dressing gown he would go to the verandah and have his chota haziri [small breakfast]. He used to take a walk up and down the verandah, and his different servants came at that time to receive their orders for the day. At seven o'clock he would go down to the swimming bath which he built just below the corner of the verandah, and then having dressed and had prayers in the oratory, he was ready for breakfast at eight o'clock. Everything was ordered with the greatest punctuality, and all the household arrangements moved as if by clock work. After he had his breakfast, his hookah was brought in and placed beside his chair… When he had finished his smoke he went to his study to write letters until the carriage was announced. This always appeared at exactly ten o'clock under the portico, and he passed through a row of servants on his way to it, one holding his hat, another his gloves, another his handkerchief, another his gold headed cane, and another his despatch box. These having been put into the carriage, his Jamadar mounted beside the coachman and drove away, with two syces standing up behind…”

William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal

<< Home